Tag: Battery Lamb (Fort Fisher NC)

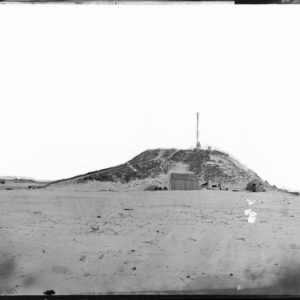

Fortwiki says: Constructions began early in 1861 on what became Battery Bolles. Major Charles P. Bolles started the fortifications and the battery was named for him. A series of officers oversaw a piecemeal expansion of the batteries until the arrival of Colonel William Lamb in July 1862. Colonel Lamb designed an “L” shaped fortification with a sea face almost a mile long and a land face that spanned the width of the point. He incorporated the existing batteries into the plan and built new batteries to fill the gaps. At the end of the sea face, he built a towering 43-foot high battery that came to be known as the Mound Battery or Battery Lamb. The completed fortifications included bombproofs, magazines, covered ways, massive traverses and protected gun positions. A separate 4 gun Battery Buchanan was built at the south end of the point to guard the inlet. By October 1864 the works were essentially complete and the batteries mostly armed. The list of batteries and armament indicates that this was a formidable fortification.

Wikipedia says: Fort Fisher was a Confederate fort during the American Civil War. It protected the vital trading routes of the port at Wilmington, North Carolina, from 1861 until its capture by the Union in 1865. The fort was located on one of Cape Fear River’s two outlets to the Atlantic Ocean on what was then known as Federal Point or Confederate Point and today is known as Pleasure Island. The strength of Fort Fisher led to its being called the Southern Gibraltar and the “Malakoff Tower of the South.”. The battle of Fort Fisher was the most decisive one of the Civil War fought in North Carolina.

Early structures

The first artillery batteries were placed in the spring of 1861, 1 mile (1.6 km) from the New Inlet. Maj. Charles Pattison Bolles supervised the works. The regional command was conformed by Gen. Theophilus H. Holmes and Maj. William H. C. Whiting (Bolles’ brother-in-law), as chief inspector of North Carolina’s defenses.

Later, when Bolles was transferred to Oak Island, Capt. William Lord deRosset took his place. deRosset brought Wilmington’s Light Infantry to the primitive artillery position, and he named the place “Bolles Battery.” Bolles Battery had a succession of interim commanders. Additionally, a training site, Camp Wyatt, was built north of the battery.

In the summer of 1861, the commander was Colonel Seawell L. Fremont. He was from the 1st NC Volunteer Artillery and Engineers. He added the following batteries along the isthmus:

Meade Battery

Zeke’s Island Battery

Anderson Battery

Gatlin Battery

Around September, the placement was formally christened “Fort Fisher”, after Col. Charles F. Fisher who was from the 6th NC Infantry and fell at the First Battle of Manassas.

Along the peninsula, the civilian population was scarce and consisted of some small family farms. The region was surrounded by pine woods. Typically, Confederate pilots would climb the tall pine trees with large ladders, spot the nearest blockade runner and then depart, meeting the incoming ship to guide it past the several passive defenses to Wilmington.

Fort Fisher was further overhauled with more powerful artillery which had been provided from Charleston. So armed, the fortress could force the Union blockade to remain well offshore, which also ensured that the Union ships could not shell the shoreline.

Fortifications

In July 1862, Col. William Lamb assumed command of the fort. Soon after arriving, he expressed some displeasure at Fort Fisher’s ongoing crude state. The fall of Norfolk increased the fort’s prominence, since Wilmington’s trading activity had to be secured. A line of soil-mounds was built which formed the Land Face, which extended along Shepherd Battery to the sea. The Sea Face was constructed later as a continuation of the previous mount line. It was extended down to a location which would constitute Mound Battery. At the intersection of both faces, the Northeast Bastion was erected, which was 30 feet (9.1 m) high. Mound Battery was the most important structure of Fort Fisher, and it was built during spring of 1863. It demanded a workforce of many hundreds and the use of a small locomotive which discharged the soil over the pile. A lighting beacon was installed at its pinnacle and was used to signal the blockade runners.

Being built mostly of soil, Fort Fisher’s structure was particularly efficient at absorbing salvos of heavy ordnance. This aspect of its design emulated the Tower of Malakoff which had been constructed at Sevastopol, Russia, during the Crimean War.

Over time, more than a thousand individuals including Confederate soldiers and slaves, had toiled at the location. The efforts had drawn more than 500 black slaves from nearby plantations. Some Native Americans, mostly Lumbee Indians, also had been impressed to assist with work on the fortifications.

After the improvements, Fort Fisher became the largest Confederate fort. In November 1863, President Jefferson Davis visited the facilities. In 1864, the complete regiment of the 36th North Carolina quartered inside Fort Fisher. In October 1864, Battery Buchanan was built.

Protecting Cape Fear’s inlet

As a rule, the Union’s warships could not sidestep Fort Fisher’s massive presence, and they were forced to remain far from shoreline because of the coastal artillery.

Land defense

The land defense extended 1,800 feet (550 m), over fifteen mounds. It held twenty-five guns which were 32 feet (10 m) above sea level. The mounds were connected by an underground network which could not be penetrated by artillery. Below, the refuge was also used as an arsenal. In front of the walls, a 9-foot (2.7 m) tall stake fence was used.

Sea defense

The sea defense extended 1 mile (1.6 km). It consisted of 22 guns at 12-foot (3.7 m)) above sea level, with 2 large batteries at the extremes. Two ancillary pieces were built at two smaller mounds. They housed a telegraphic office and a bomb-resistant hospital.

Battery Buchanan

Battery Buchanan was a small but impressive fortification which was constructed in 1864 at the furthest tip of the peninsula (Confederate Point), overlooking Cape Fear’s New Inlet. It was named for Admiral Franklin Buchanan of the Confederate Navy.

Weapons

Along the sea defense there were numerous columbiad 8 inch cannon, a few 10 inch columbiads and a mixture of rifled 32-pounders and Brooke Rifles. An 8 inch Blakeley Rifle was mounted in the Northeast Bastion and an innovative 150-pound Armstrong Gun was placed along the sea face. Barbettes were installed around each of the cannon, and the cannon were placed along both faces of Shepherd Battery and Mound Battery. The land defenses included 4.5 inch Parrott Rifles at the Shepherd Battery and two 24-pound Coehorn Mortars and one 10 inch seacoast mortar along the land face. 12-pound Napoleon-M1857 and a 3 inch Parrott Rifle were stationed near the entrance. The middle sally port along the fort’s land face was protected by two 12-pounders.

Expedition to Fort Fisher

The Union planned to seize Wilmington after Mobile, Alabama fell in August 1864. By September 1864, a variety of sources—such as the Confederate intelligence and some Union newspapers—conjectured an imminent Union attack on either Charleston or Wilmington.

2,400 men were at Fort Fisher. They were insufficiently trained for defending against a land attack. Because of demands from other battlefronts—particularly Richmond—the defenders were being slowly replaced by local forces from North Carolina. For example, the Cape Fear River was further filled with “torpedoes”, and a breastwork was built at the northern end of the fortification in order to contain any landing forces.

Because of his alleged alcoholism and other personal problems, Whiting was removed from command by Lee, and General Braxton Bragg was assigned as commander for the region. In November 1864, Bragg was ordered to join the battle against William T. Sherman in Georgia. For this, Bragg detached 2,000 troops from the already feeble Wilmington defensive lines. When Ulysses S. Grant was informed about this specific maneuver, he began formulating the definitive plan of invasion.

First battle

On December 15, 1864, Jefferson Davis supposed that Wilmington had not yet been attacked because it would have demanded “the withdrawal of too large a [Union] force from operations against points which they deem more important to us.” Otherwise, “fleets and armies” would have already been “at the mouth of the Cape Fear.”

In December 1864, Union Major General Benjamin Butler, together with the Expeditionary Corps of the Army of the James, was detached from the Virginia theater for an amphibious mission to capture Fort Fisher. He was joined by Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, who commanded Union naval forces already in the region.

After being informed about the large Union army heading toward Wilmington, General Lee ordered Major General Robert Hoke’s Division to Fort Fisher. Also, Hoke took command of all Confederate forces in the Wilmington area.

The Union attack started on December 24, 1864 with a naval bombardment. The firepower of Fort Fisher was temporarily silenced because some of its gun positions exploded. This allowed the Navy to land Union infantry. The landing force was intercepted by the arrival of Hoke’s troops. The Union attack was effectively thwarted and, on December 27, Benjamin Butler ordered the withdrawal of his 1,000 soldiers who were still on the beach. This was in disobedience to Grant’s orders, which were to besiege the fort if the assault failed. Because Butler disobeyed his orders, he was relieved of command by Grant.

Second battle

Butler was replaced by Major General Alfred Terry, and the operation was dubbed “Terry’s expedition.” Admiral Porter was again in charge of the naval attack. They waited until January 12, 1865, for the second attempt.

The new attack started with a heavy, continual bombardment from Porter’s 56 ships. This initially targeted both of Fort Fisher’s fronts. On January 13, Porter shifted fire to the fort itself, while Terry’s infantry force of 8,000 soldiers commanded by Adelbert Ames landed north of the fort. By mid-afternoon, the fort was effectively isolated. Porter’s ships fired throughout the night and the following day. On January 15, a second force of 1,600 sailors and 400 Marines commanded by LCdr. Kidder Breese was landed to the northeast of the fort.

At 3 p.m., Ames’ infantry attacked at the northern, land face. At the same time, Breese’s landing force attacked the fort’s northeast bastion (the point where the land face met the sea face). Breese’s attack was repulsed, but not before drawing the defenders’ attention from the attack on the northern face. There the Union infantry entered the fortification through Shepherd Battery. The Confederate defenders found themselves battling inside their walls, and were forced to retreat.

Altogether, the land battle lasted six hours. At nighttime, General William Whiting, who had been wounded during the battle, surrendered as Commander of the District of Cape Fear. He was then imprisoned, and died in prison on March 10, 1865. The Confederates who had been captured and were not wounded were taken to the Elmira Prison located in New York, and assigned to Company E, 3rd Division of Prisoners. Those Confederates that were wounded were admitted to Hammond General Hospital and upon recovery were discharged and transferred to the main prison complex. Hammond General Hospital was outside the prison compound at Point Lookout, Maryland. Many of the guards in the prison at Point Lookout were former slaves that had joined the Union ranks.

Aftermath

With the fall of Fort Fisher, the trading route to Wilmington was cut, as was the supply line for General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Following the fall of Fort Anderson on the Cape Fear River the Union occupied Wilmington definitively on February 22, 1865.

The magazine explosion

Shortly after sunrise on January 16, 1865, Fort Fisher’s main magazine exploded — a tremendous blast that killed at least 200 men of both sides. The tragedy sparked a heated debate, as the Union victors were eager to blame the Confederates for dastardly behavior. But the previous night’s giddy celebration among the Federals had spawned many a drunken reveler; and the accident occurred despite the posting of guards at the fort’s magazines.

An official Court of Inquiry determined the following:

FINDINGS.

After mature deliberation upon the foregoing evidence the court finds that the following are the main facts, viz:

Immediately after the capture of the fort General Ames gave orders to Lieut. Samuel M. Zent, Thirteenth Indiana Volunteers, through Capt. George W. Huckins, Fourth New Hampshire Volunteers, acting assistant adjutant-general, Third Brigade, Second Division, to place guards on all the magazines and bombproofs. Lieutenant-Colonel Zent commenced on the northwest corner of the fort next [to] the river, following the traverses round, and placed guards on thirty-one entrances under the traverses. The main magazine which afterward exploded, being in the rear of the traverses, escaped his notice, and consequently had no guards from his regiment or any other. That soldiers, sailors and marines were running about with lights in the fort, entering bombproofs with these lights, intoxicated and discharging firearms. That personas were seen with lights searching for plunder in the main magazine some ten of fifteen minutes previous to the explosion. The court do not [sic] attach any importance to the report that a magnetic wire connected this work [fort] with some work on the opposite side of the Cape Fear River.

OPINION.

The opinion of the court, therefore, is that the explosion was the result of carelessness on the part of persons to them unknown. The court then adjourned sine die

— JOSEPH C. ABBOTT,

Brevet Brigadier-General, U.S. Volunteers, President of Court.

— GEORGE F. TOWLE,

Captain Fourth New Hampshire Volunteers, Acting Assistant Inspector-General and Recorder.,

United States War Department. The War of the Rebellion, A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. (Series I, Vol. 46, Reports, pp. 430–431).

Showing all 3 resultsSorted by latest