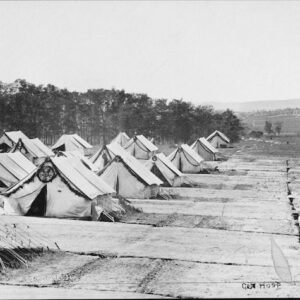

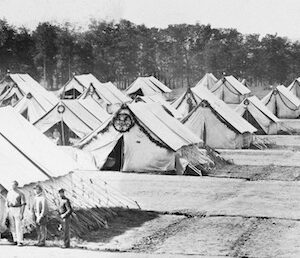

Tag: Camp Letterman (Gettysburg PA)

Wikipedia says: Camp Letterman was an American Civil War military hospital, which was erected near the Gettysburg Battlefield to treat more than 14,000 Union and 6,800 Confederate wounded of the Battle of Gettysburg at the beginning of July, 1863.

One of the most important military engagements of the American Civil War, the Battle of Gettysburg was waged over the first three days of July 1863 between the United States’ Army of the Potomac, which was commanded by Major-General George Gordon Meade, and the Confederate States of America’s Army of Northern Virginia, which had been marched north into Maryland and Pennsylvania by its commanding Major-General Robert E. Lee. Clashing near the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the conflict quickly escalated into an intense combat situation with multiple, memorable skirmishes and battles, including Seminary Ridge, Little Round Top and Pickett’s Charge. Meade’s Union troops ultimately won the three-day, tide-turning engagement, which resulted in the deaths of more than 3,100 Union and 4,700 Confederate troops with wounded men totaling more than 14,500 (Union) and 12,600 (Confederate).

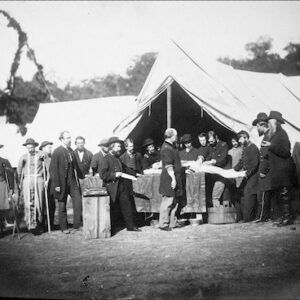

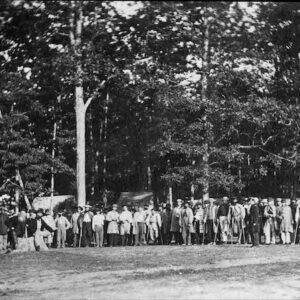

In the aftermath, when Union military leaders realized that the farms, private homes, churches, and other buildings in and around the town of Gettysburg which had been pressed into service as makeshift regimental hospitals were so overwhelmed by the numbers of dying and wounded, and that many of the soldiers who had been unable to find shelter were being cared for in gardens and other outdoor spaces, they quickly secured approval from their superiors to create a new general hospital. Built sometime after July 8, 1863, it opened on July 22, and was named Camp Letterman in honor of Jonathan Letterman, M.D., the “Father of Battlefield Medicine” who created medical management procedures which transformed not only Civil War-era medicine, but the medical care for thousands of soldiers in subsequent wars, the tents of the hospital complex were erected east of Gettysburg. Union Army surgeons, nurses and members of the U.S. Sanitary Commission then began rendering care to soldiers from both sides of the conflict, ultimately evaluating and treating all of the wounded who had been transported from the various battle sites around Gettysburg. Meals were prepared for the men by a sizeable force of cooks while guards kept the peace among those who were ambulatory. Those needing more advanced treatment or who were doing well enough to be moved out for convalescent care were subsequently sent on to the Union’s larger hospitals in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

By January 1864, Camp Letterman was no longer needed by the Union Army; so, the facility was closed.

In June 2018, the Pennsylvania House of Representatives voted unanimously to pass House Resolution No. 998 to honor Camp Letterman for the role it played in treating the large number of casualties who had been wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg during July 1863.

The role of women at Camp Letterman

According to accounts by Sophronia Bucklin and Cornelia Hancock, two of the seven women who served at nurses at Camp Letterman following the Battle of Gettysburg, an additional 30-plus women served in capacities other than nursing (making the combined total of women at Camp Letterman roughly 40). According to Hancock, she and three other women were assigned to one of the hospital tents. Per Bucklin, the nurses’ accommodations were spartan:

“My tent contained an iron bedstead, on which for a while I slept with the bare slats beneath, and covered with sheets and blanket. I afterwards obtained a tick and pillow, from the Sanitary Commission, and filled them with straw, sleeping in comparative comfort. I soon found, however, that the wounded needed these more than I, and back I went to the hard slats again, this time without the sheets, which were given for the purpose of changing a patient’s blood-saturated bed. As time passed, and the heavy rains fell, sending muddy rivulets through our tents, we were often obliged in the morning to use our parasol handles to fish up our shoes from the water before we could dress ourselves. A tent cloth was afterwards put down for a carpet, and a Sibley stove set up to dry our clothing. These were oft times so damp, that it was barely possible to draw on the sleeves of our dresses. By and by I had the additional comfort of two splint-bottomed rocking chairs, which were given me by convalescent patients, who had brought them to the hospital for their own use, and on departing left them a legacy to me. With these a stand was added to my furniture. I here learned how few are nature’s real wants. I learned how much, which at home we call necessary, can be lopped off, and we still be satisfied; how sleep can visit our eyelids, and cold be driven away with the fewest comforts around us.”

Another of the seven nurses, Margaret Hamilton, rendered care to patients who were isolated in Letterman’s smallpox ward. Tillie Pierce, a teenager at the time of the battle, also reportedly nursed wounded men at Camp Letterman. An eyewitness to troop movements and various stages of the battle, she was the daughter of a Gettysburg butcher, and later went on to write, At Gettysburg, or What A Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle: A True Narrative.”

One of those who provided other services was Rebecca Lane Pennypacker Price who, as a member of the Phoenixville Union Relief Society, had been involved in relief efforts since the beginning of the war, recruiting women to sew and knit clothing items for Union troops, organizing financial and other types of donation drives, and personally delivering supplies to troops thanks to the help of a travel pass that was issued to her by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin. She then progressed on to provide nursing care at various Union hospitals, where she became acquainted with, and respected by, several military physicians. Initially partnering with members of her relief society and the Christian Commission to collect and transport supplies to Gettysburg following the battle, she quickly became a helper to the Union’s ambulance corps, providing comfort to men who were awaiting transport from battle sites, helping to distract those awaiting amputation and other surgical procedures, and writing letters on behalf of dying soldiers who wanted to transmit their final thoughts and to their families. As physicians she knew from previous battlefield assignments came to realize that she was on site at Letterman, she increasingly became involved with caring for hopeless medical cases, rendering end-of-life care to men from both sides of the conflict who were too grievously wounded to survive their injuries.

Showing all 10 resultsSorted by latest