Tag: Cavalry Corps

Wikipedia says: Two corps of the Union Army were called Cavalry Corps during the American Civil War. One served with the Army of the Potomac; the other served in the various armies of the western theater of the war.

In contrast to the Confederacy, which early on spawned such brilliant cavalry leaders as J.E.B. Stuart, Nathan B. Forrest, and John S. Mosby, the Union high command initially failed to understand the proper way to use cavalry during the early stages of the war. At the time, cavalry units in the Union armies were generally directly attached to infantry corps, divisions, and “wings” to be used as “shock troops,” and essentially played minimal roles in early Civil War campaigns. The Union cavalry was disgraced by Stuart’s raids during the Peninsular, Northern Virginia, and Maryland Campaigns, where Stuart was able to ride around the Union Army of the Potomac with feeble resistance from the scant Federal cavalry. The Federals rarely even used cavalry as scouts or raiders in the early days of the war. Only a handful of Union cavalry officers, George Bayard, Benjamin Grierson, and John Buford among them, distinguished themselves in a positive way in the first two years of the war.

Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac

After the disastrous Fredericksburg Campaign, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker took command of the Army of the Potomac. One of Hooker’s positive contributions was in creating a unified cavalry command in April 1863. Other than at Antietam, where the cavalry had been combined into a single division for a planned (but unengaged) attack on Lee’s center, the Union cavalry had not been unified to date. Hooker organized three previously unrelated divisions into a single corps of cavalry, placing it under the unified command of George Stoneman. Hooker also began outfitting them with Sharps and Smith breechloading rifles, and, in a couple cases, with Spencer repeating rifles, giving them an advantage in firepower over the Confederates.

Chancellorsville

Despite Hooker’s organizational changes, the new Cavalry Corps gave a poor accounting of itself during the Chancellorsville Campaign. Hooker ordered Stoneman to launch a diversionary raid against Richmond to distract Stuart’s cavalry, but the raid was unsuccessful, resulting in the debacle at Kelly’s Ford—an indecisive battle that forced the raid’s premature abortion. Worse, Hooker kept only a single division—under Alfred Pleasonton—with the main army to use as scouts or screens while traveling through the dense “Wilderness,” accounting in part for the success of Stonewall Jackson’s famous flank march on May 2.

Gettysburg

Stoneman and division commander William W. Averell were sacked after Chancellorsville, and replaced, respectively, by Alfred Pleasonton and David McM. Gregg.

During the early stages of the Gettysburg Campaign, the cavalry first gained notice and respect from their Confederate foes at the Battle of Brandy Station, on June 9, 1863—the largest primarily cavalry engagement ever fought on the American continent. Though Pleasonton’s men were ultimately defeated, this battle established the Union cavalry as no longer inefficient and overmatched, but a foe to be reckoned with. Numerous other changes were made in brigade command as the campaign progressed, and a number of young officers were promoted to brigade command, including Wesley Merritt, George Armstrong Custer, and Elon J. Farnsworth.

Later in the campaign, Judson Kilpatrick’s division, sent from the XXII Corps, joined up with the army. The cavalry divisions engaged Stuart in a number of fierce, hotly contested battles at Aldie, Middleburg, Upperville, Hanover, and several smaller engagements.

It was John Buford’s cavalry division which touched off the Battle of Gettysburg itself, engaging the Confederate division of Henry Heth to prevent him from occupying Gettysburg on July 1. Buford’s troopers played a major part in slowing Heth’s initial advance, and, after being relieved by infantry, spent the rest of July 1 screening and scouting. His division was sent to guard the army’s supply trains for the remainder of the battle, but the divisions of Gregg and Kilpatrick remained on the field. On July 3, concurrent with Pickett’s Charge, Gregg’s division (with Custer’s brigade of Kilpatrick’s division) engaged Stuart east of Gettysburg and checked repeated Confederate advances. However, on the same day south of Gettysburg, Kilpatrick ordered a futile charge by the brigade of Elon J. Farnsworth against Confederate positions on Big Round Top, resulting in Farnsworth’s death and heavy casualties among his men.

The cavalry continued to perform aggressively in George Meade’s pursuit of Lee into Virginia. In an irony, the last battle of the campaign, at Falling Waters, occurred between the remnants of Heth’s and Buford’s divisions.

1864

If any doubts remained as to the Union cavalry’s equality with its Southern counterparts, they were dispelled during Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign. The Cavalry Corps, now consisting of four divisions, was placed under command of the fiery Phillip Sheridan. In the early stages of the campaign, they engaged Stuart’s cavalry in a series of ferocious, bloody battles, killing General Stuart at Yellow Tavern. Stuart’s successor, Wade Hampton, proved to be an equally formidable foe at the battles of Haw’s Shop, Old Church, Trevilian Station, and Battle of Saint Mary’s Church. The Union cavalry spent most of the Petersburg Campaign trying to cut rail lines from Petersburg and Richmond. The bulk of the cavalry was sent under Sheridan to join the Army of the Shenandoah during Sheridan’s campaign against Jubal Early in the summer of 1864 (see Valley Campaigns of 1864).

After Sheridan’s highly successful campaign concluded, the cavalry corps—along with the rest of his army—returned to join the Army of the Potomac. For the next several months, they resumed their slow but steady snipping off of Confederate supply and communication lines.

End of the war

The most conspicuous part played by the cavalry during the closing days of the war occurred in the week of March 25–April 1, 1865, when Lee, in a series of bold but understrength and futile counterattacks, tried to break through the Union lines at Fort Stedman. The IX Corps repulsed the attack. A week later, at Five Forks, Sheridan’s cavalry played a decisive role in repulsing George Pickett’s last desperate attack and routing his division. Sheridan and his men continued to play a major part in harassing Lee’s army as it withdrew to Appomattox Court House. In the last battles fought in Virginia, it engaged Confederate cavalry in a desultory skirmish at Appomattox Station on April 8, and took part in a small skirmish the following day at the Battle of Appomattox Courthouse, which effectively concluded the war in Virginia.

Western Cavalry Corps

As in the East, the various Union commanders in the West generally used cavalry poorly during the first two years of the war; cavalry was again parcelled out to be attached to infantry corps as “shock troops” and scouts. Unlike in the East, where the cavalry proved itself the equal of its foes by the summer of 1863, the Union cavalry in the West struggled to identify an equal to Nathan B. Forrest, and were defeated in most of their major engagements. Grierson’s famous raid during the Vicksburg Campaign was an aberration and far from the norm.

The first attempt at a unified cavalry command occurred in late 1862/63, when William S. Rosecrans, commanding the Army of the Cumberland, organized all of his cavalry into a single division, acting as a separate command from the infantry, under the command of David S. Stanley. This new division fought respectably, if unremarkably, at Stones River. During the Tullahoma Campaign this cavalry division was expanded to corps size. Stanley commanded the corps with Robert B. Mitchell and John B. Turchin commanding the 1st and 2nd Divisions respectively. Mitchell commanded the corps at Chickamauga while Edward M. McCook and George Crook commanded the divisions.

During the Atlanta Campaign, General William T. Sherman reorganized the cavalry of the armies of the Cumberland and Tennessee into four “columns”, with no overall commander (the columns commanded by Stoneman, Kilpatrick, Edward McCook, and Israel Garrard). The cavalry continued to perform in a mediocre-at-best fashion, failing an abortive raid to free Andersonville prison camp and being repeatedly defeated by Joseph Wheeler’s Confederate cavalry in a series of fights in central Georgia. During Sherman’s March to the Sea, Kilpatrick’s division remained with the army, serving again with a lack of real distinction, while the rest of the cavalry went north with George Thomas to repel John B. Hood’s invasion of Tennessee, taking part in the actions at Spring Hill and Murfreesboro.

In December 1864, just before the Battle of Nashville, a formal cavalry corps was finally organized, under Brevet Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson. It performed decently at Nashville, but, as before, failed to distinguish itself to any real degree. Wilson led the corps in one of the final battles of the war April 16, 1865, at the Battle of Columbus, where, fighting dismounted against Forrest’s troopers, they were able to defeat their enemy–the only time Federal cavalry defeated General Forrest.

The rest of the Union field armies typically had no unified large-scale cavalry commands as such, other than a corps-sized command, under Pleasonton, that was briefly organized by the Department of Missouri to defend that state against Sterling Price’s expedition in 1864.

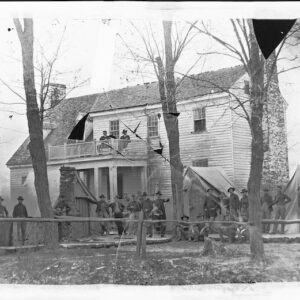

Showing 1–16 of 54 resultsSorted by latest

-

Image ID: AYLX

$0.99 -

Image ID: AYMD

$0.99 -

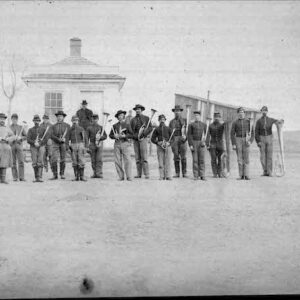

Image ID: ANHH

$1.99 – $6.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

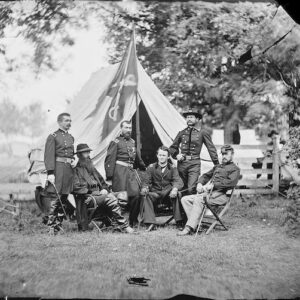

Image ID: ANJW

$0.99 -

Image ID: ANJX

$0.99 -

Image ID: ATTX

$0.99 -

Image ID: ANNO

$6.99 -

Image ID: AXZL

$0.99 -

Image ID: AXZO

$0.99 -

Image ID: AXZP

$0.99 -

Image ID: AHQI

$4.99 – $5.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: AIFZ

$0.99 – $4.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: AMHD

$0.99 -

Image ID: AUCS

$1.99 -

Image ID: AROA

$5.99 -

Image ID: AHAU

$6.99