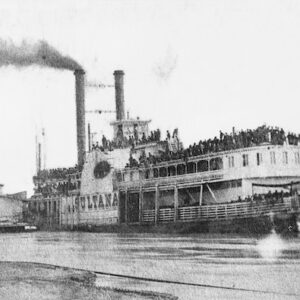

Tag: side-wheeler Sultana

Gibson and Gibson, Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels Steam and Sail Employed by the Union Army, 1861-1868 says: SULTANA; sidewheel steamer; 1300 tons. Chartered Feb 12-Mar 4, 1864; Mar 20-21, 1864; Apr 29-May 13, 1864; Apr 22-Apr 24, 1865. Vessel blew up near Memphis, Tennessee, Apr 24, 1865. Loss of life was estimated at 1200 officers and soldiers. These men were mainly ex-prisoners of war, many from Andersonville.

Gibson and Gibson, Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels Steam and Sail Employed by the Union Army, 1861-1868 says: SULTANA; sidewheel steamer; 1300 tons. Chartered Feb 12-Mar 4, 1864; Mar 20-21, 1864; Apr 29-May 13, 1864; Apr 22-Apr 24, 1865. Vessel blew up near Memphis, Tennessee, Apr 24, 1865. Loss of life was estimated at 1200 officers and soldiers. These men were mainly ex-prisoners of war, many from Andersonville.

Wikipedia says: Sultana was a commercial side-wheel steamboat which exploded and sank on the Mississippi River on April 27, 1865, killing 1,168 people in the worst maritime disaster in United States history.

Constructed of wood in 1863 by the John Litherbury Boatyard in Cincinnati, she was intended for the lower Mississippi cotton trade. The steamer registered 1,719 tons and normally carried a crew of 85. For two years, she ran a regular route between St. Louis and New Orleans and was frequently commissioned to carry troops. Although designed with a capacity of only 376 passengers, she was carrying 2,137 when three of the boat’s four boilers exploded and she burned to the waterline and sank near Memphis, Tennessee. The disaster was overshadowed in the press by events surrounding the end of the American Civil War, including the killing of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth just the day before, and no one was ever held accountable for the tragedy.

Construction

Launched on January 3, 1863, the Sultana was the fifth river steamboat to bear the name. Built for speed and capacity, the vessel measured 260 feet long, was 39 feet wide at the base and 42 feet wide at the beam, displaced 719 tons, and had a 7-foot draft. Her two side-mounted paddle wheels were driven by four tubular, or fire-tube, boilers. Introduced in 1848, they were capable of generating twice as much steam per fuel load as conventional flue boilers. Each fire-tube boiler was 18 feet long and 46 inches in diameter and contained 24 five-inch flues, tubes that ran from the firebox to the chimney.

The economic advantages came with a safety tradeoff. The water levels in a tubular system had to be carefully maintained at all times. The areas between the many flues clogged easily, and the sediment and mineral buildup around the tubes and boiler sides, especially heavy when the river water used in the system carried much sediment, was difficult to scrape off. Even the slightest dip in water level could cause hot spots leading to metal fatigue, greatly increasing the risk of an explosion. With the typical steamboat construction, made up of layers of highly flammable lightweight wood covered with paint and varnish, the likelihood was that any such incident would be catastrophic.

Disaster

Background

Under the command of Captain James Cass Mason of St. Louis, Sultana left St. Louis on April 13, 1865, bound for New Orleans, Louisiana. On the morning of April 15, she was tied up at Cairo, Illinois, when word reached the city that President Abraham Lincoln had been shot at Ford’s Theater. Immediately, Captain Mason grabbed an armload of Cairo newspapers and headed south to spread the news, knowing that telegraphic communication with the South had been almost totally cut off because of the war.

Upon reaching Vicksburg, Mississippi, Mason was approached by Captain Reuben Hatch, the chief quartermaster at Vicksburg. Hatch had a deal for Mason. Thousands of recently released Union prisoners of war who had been held by the Confederacy at the prison camps of Cahaba near Selma, Alabama, and Andersonville in southwest Georgia, had been brought to a small parole camp outside of Vicksburg to await release to the North. The U.S. government would pay $2.75 per enlisted man and $8 per officer to any steamboat captain who would take a group north. Knowing that Mason was in need of money, Hatch suggested that he could guarantee Mason a full load of about 1,400 prisoners if Mason would agree to give him a kickback. Hoping to gain much money through this deal, Mason quickly agreed to the offered bribe.

Leaving Vicksburg, Sultana traveled downriver to New Orleans, continuing to spread the news of Lincoln’s assassination. On April 21, Sultana left New Orleans with about 70 cabin and deck passengers, along with a small amount of livestock. She also carried a crew of 85. About ten hours south of Vicksburg, one of Sultana’s four boilers sprang a leak. Under reduced pressure, the steamboat limped into Vicksburg to get the boiler repaired and to pick up her promised load of prisoners.

Faulty boiler repair

While the paroled prisoners, primarily from the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee and West Virginia, were brought from the parole camp to Sultana, a mechanic was brought down to work on the leaky boiler. Although the mechanic wanted to cut out and replace a ruptured seam, Mason knew that such a job would take a few days and cost him his precious load of prisoners. By the time the repairs would be completed, the prisoners would have been sent home on other boats. Instead, Mason and his chief engineer, Nathan Wintringer, convinced the mechanic to make temporary repairs, hammering back the bulged boiler plate and riveting a patch of lesser thickness over the seam. Instead of taking two or three days, the temporary repair took only one. During her time in port, and while the repairs were being made, Sultana took on the paroled prisoners.

Overloaded

Although Hatch had suggested that Mason might get as many as 1,400 released Union prisoners, a mix-up with the parole camp books and suspicion of bribery from other steamboat captains caused the Union officer in charge of the loading, Captain George Augustus Williams, to place every man at the parole camp on board Sultana, believing the number to be less than 1,500. Although Sultana had a legal capacity of only 376, by the time she backed away from Vicksburg on the night of April 24, she was severely overcrowded with 1,960 paroled prisoners, 22 guards from the 58th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 70 paying cabin passengers, and 85 crew members, for a total of 2,137 people. Many of the paroled prisoners had been weakened by their incarceration in the Confederate prison camps and associated illnesses but had managed to gain some strength while waiting at the parole camp to be officially released. The men were packed into every available space, and the overflow was so severe that in some places, the decks began to creak and sag and had to be supported with heavy wooden beams.

Sultana spent two days traveling upriver, fighting against one of the worst spring floods in the river’s history. At some places, the river overflowed the banks and spread out three miles wide. Trees along the river bank were almost completely covered, until only the very tops of the trees were visible above the swirling, powerful water. On April 26, Sultana stopped at Helena, Arkansas, where photographer Thomas W. Bankes took a picture of the grossly overcrowded vessel. Sultana subsequently arrived at Memphis, Tennessee, around 7:00 PM, and the crew began unloading 120 tons of sugar from the hold. Near midnight, Sultana left Memphis, leaving behind about 200 men. She then went a short distance upriver to take on a new load of coal from some coal barges, and then at about 1:00 AM started north again.

Explosion

At around 2:00 AM on April 27, 1865, when Sultana was about seven miles north of Memphis, its boilers suddenly exploded. First one boiler exploded, followed a split-second later by two more.

The enormous explosion of steam came from the top rear of the boilers and went upward at a 45-degree angle, tearing through the crowded decks above and completely demolishing the pilothouse. Without a pilot to steer the boat, Sultana became a drifting, burning hulk. The terrific explosion flung some of the deck passengers into the water and destroyed a large section of the boat. The twin smokestacks toppled over; the starboard one backwards into the blasted hole, and the port one forward onto the crowded forward section of the upper deck. The forward part of the upper deck was crushed down onto the middle deck, killing and trapping many in the wreckage. Fortunately the sturdy railings around the twin openings of the main stairway prevented the upper deck from crushing down completely onto the middle deck. The men located around the twin openings quickly crawled under the wreckage and down the main stairs. Further back, the collapsing decks formed a slope that led down into the exposed furnace boxes. The broken wood caught fire and turned the remaining superstructure into an inferno. Survivors of the explosion panicked and raced for the safety of the water, but in their weakened condition they soon ran out of strength and began to cling to each other. Whole groups went down together.

Rescue attempts

While this fight for survival was taking place, the southbound steamer Bostona (No. 2), built in 1860 but coming downriver on her maiden voyage after being refurbished, arrived at about 2:30 AM, a half hour after the explosion, and rescued scores of survivors. At the same time, dozens of people began to float past the Memphis waterfront, calling for help until they were noticed by the crews of docked steamboats and U.S. warships, who immediately set about rescuing the survivors. Eventually, the hulk of Sultana drifted about six miles to the west bank of the river and sank at around 9:00 AM near Mound City and present-day Marion, Arkansas, about seven hours after the explosion. Other vessels joined the rescue, including the steamers Silver Spray, Jenny Lind, and Pocohontas, the navy ironclad Essex and the sidewheel gunboat USS Tyler.

Passengers who survived the initial explosion had to risk their lives in the icy spring runoff of the Mississippi or burn with the boat. Many died of drowning or hypothermia. Some survivors were plucked from the tops of semi-submerged trees along the Arkansas shore. Bodies of victims continued to be found downriver for months, some as far as Vicksburg. Many bodies were never recovered. Most of Sultana’s officers, including Captain Mason, were among those who perished.

Casualties

The exact death toll is unknown, although the most recent evidence indicates 1,168. On May 19, 1865, less than a month after the disaster, Brigadier General William Hoffman, Commissary General of Prisoners who investigated the disaster, reported an overall loss of soldiers, passengers, and crew of 1,238. In February 1867, the Bureau of Military Justice placed the death toll at 1,100. In 1880, the 51st Congress of the United States, in conjunction with the War Department, Pensions and Records Department, reported the loss of life aboard the Sultana as 1,259. The official count by the United States Customs Service was 1,547. In 1880, the War Department, Pensions and Records Department, placed the number of survivors at 931, but the most recent research places the number at 969. The dead soldiers were interred at the Fort Pickering cemetery, located on the south shore of Memphis. A year later, when the U.S. government established the Memphis National Cemetery on the northeast side of the city, the bodies were moved there. Three civilian victims of the wreck of Sultana are interred at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis.

Survivors

About 760 survivors were transported to hospitals in Memphis. Since Memphis had been captured by Federal forces in 1862 and turned into a supply and recuperation city, there were numerous hospitals in the city with the latest medical equipment and trained personnel. Of the roughly 760 people taken to Memphis hospitals, there were only 31 deaths between April 28 and June 28. Newspaper accounts indicate that the people of Memphis had sympathy for the victims although they were in an occupied city. The Chicago Opera Troupe, a minstrel group that had traveled upriver on Sultana before getting off at Memphis, staged a benefit, while the crew of the gunboat Essex raised $1,000.

In December 1885, the survivors living in the northern states of Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio began attending annual reunions, forming the National Sultana Survivors’ Association. Eventually, the group settled on meeting in the Toledo, Ohio, area. Perhaps inspired by their Northern comrades, a Southern group of survivors, men from Kentucky and Tennessee, began meeting in 1889 around Knoxville, Tennessee. Both groups met as close to the April 27 anniversary date as possible, corresponded with each other, and shared the title National Sultana Survivors’ Association.

By the mid-1920s, only a handful of survivors were able to attend the reunions. In 1929, only two men attended the Southern reunion. The next year, only one man showed up. The last Northern survivor, Private Jordan Barr of the 15th Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment, died on May 16, 1938, at age 93. The last of the Southern survivors, and last overall survivor, was Private Charles M. Eldridge of the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry, who died at his home at age 96 on September 8, 1941, more than 76 years after the Sultana disaster.

Causes

The official cause of the Sultana disaster was determined to be mismanagement of water levels in the boilers, exacerbated by the fact that the vessel was severely overloaded and top-heavy. As the steamboat made her way north following the twists and turns of the river, she listed severely to one side, then to the other. Her four boilers were interconnected and mounted side-by-side, so that if the boat tipped sideways, water would tend to run out of the highest boiler. With the fires still going against the empty boiler, this created hot spots. When the boat tipped the other way, water rushing back into the empty boiler would hit the hot spots and flash instantly to steam, creating a sudden surge in pressure. This effect of careening could have been minimized by maintaining high water levels in the boilers. The official inquiry found that the boat’s boilers exploded because of the combined effects of careening, low water levels, and a faulty repair to a leaky boiler made a few days earlier.

The most recent investigation into the cause of the disaster by Pat Jennings, principal engineer of Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company, which came into existence in 1866 because of the Sultana explosion, determined that three main factors led to the explosion:

1) The type of metal used in the construction of the boilers – Charcoal Hammered No. 1, which tends to become brittle with prolonged heating and cooling. Charcoal Hammered No. 1 was no longer used for the manufacture of boilers after 1879.

2) The use of the sediment-laden Mississippi River water to feed the boilers. The sediment tended to settle on the bottom of the boilers or clog between the flues and leave hotspots.

3) The design of the boilers. Sultana had tubular boilers filled with 24 horizontal 5-inch flues. Being so closely packed within the 48-inch diameter boilers tended to cause the muddy sediment to form hot pockets. They were extremely difficult to clean. Tubular boilers were discontinued from use on steamboats plying the Lower Mississippi after two more steamboats with tubular boilers exploded shortly after the Sultana.

Traditional alternative theories

In 1888, a St. Louis resident named William Streetor claimed that his former business partner, Robert Louden, made a confession of having sabotaged the Sultana by the use of a coal torpedo while they were drinking in a saloon. Louden, a former Confederate agent and saboteur who operated in and around St. Louis, had been responsible for the burning of the steamboat Ruth. (Thomas Edgeworth Courtenay, the inventor of the coal torpedo, was a former resident of St. Louis and was involved in similar acts of sabotage against Union shipping interests. However, Courtenay’s great-great-grandson, Joseph Thatcher, who wrote a book on Thomas Courtenay and the coal torpedo, denies that a coal torpedo was used. “If you read my book… you will note that we do not claim the Sultana, nor did Courtenay.”) Supporting Louden’s claim was the fact that what appeared to be a piece of an artillery shell was recovered from the sunken wreck. Louden’s claim is controversial, however, and most scholars support the official explanation. The location of the explosion, from the top rear of the boilers, far away from the fireboxes, tends to indicate that Louden’s claim of sabotage of an exploding coal torpedo in the firebox was pure bravado.

Two years before William Streetor’s claim that Louden sabotaged Sultana, there was a claim that 2nd Lt. James Worthington Barrett, an ex-prisoner and passenger on the steamboat, had caused the explosion. Barrett was a veteran of the Mexican–American War and had fought bravely with his regiment until he was captured at Franklin, Tennessee. He was injured on the Sultana and was honorably discharged in May 1865. There is no apparent motive for him to have blown up the boat, especially while on board.

In 1903, another person came out with a report that the Sultana had been sabotaged by a Tennessee farmer who lived along the river and cut wood for passing steamboats. After a few Union gunboats filled up their bunkers but refused to pay, the farmer supposedly hollowed out a log, filled it with gunpowder and then left the lethal log on his woodpile. As stated in the 1903 newspaper article, the log was mistakenly taken by the Sultana. However, the Sultana was a coal-burning boat, not a wood-burner.

An episode of History Detectives that aired on July 2, 2014, reviewed the known evidence, thoroughly disputed a theory of sabotage, and then focused on the question of why the steamboat was allowed to be crowded to several times its normal capacity before departure. The report blamed quartermaster Hatch, an individual with a long history of corruption and incompetence, who was able to keep his job through political connections: he was the younger brother of Illinois politician Ozias M. Hatch, an advisor and close friend of President Lincoln. Throughout the war, Reuben Hatch had shown incompetence as a quartermaster and competence as a thief, bilking the government out of thousands of dollars. Although brought up on courts-martial charges, Hatch managed to get letters of recommendation from no less reputable personages than President Lincoln himself and from General of the Army Ulysses S. Grant. The letters reside in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. After the disaster, Hatch refused three separate subpoenas to appear before Captain Speed’s trial and give testimony. Hatch died in 1871, having escaped justice because of his numerous highly placed patrons—including two presidents.

Lack of accountability

In spite of the magnitude of the disaster, no one was ever formally held accountable. Captain Frederick Speed, a Union officer who sent the 1,960 paroled prisoners into Vicksburg from the parole camp, was charged with grossly overcrowding Sultana and found guilty. However, the guilty verdict was overturned by the judge advocate general of the Army on grounds that Speed had been at the parole camp all day and had not personally placed a soldier on board the Sultana. Captain George Williams, who had placed the men on board, was a regular Army officer, and the military refused to go after one of their own. And Captain Hatch, who had concocted a bribe with Captain Mason to crowd as many men onto the Sultana as possible, had quickly quit the service to avoid a court-martial. The master of the Sultana, Captain Mason, who was ultimately responsible for dangerously overloading his vessel and ordering the faulty repairs to her leaky boiler, had died in the explosion. In the end, no one was ever held accountable for the greatest maritime disaster in United States history.

Showing the single result